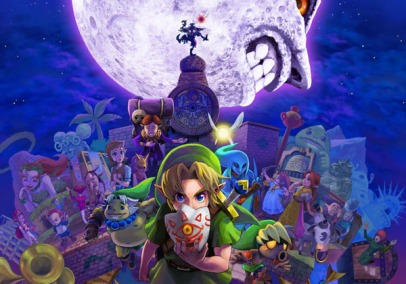

The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is unquestionably one of the deepest, most profound entries of The Legend of Zelda franchise. Dealing with topics ranging from death, love, friendship, regret, and loneliness, among others, Majora’s Mask’s mature themes touch on real-world issues, despite its fantastical setting and story. Some of the most noteworthy quotes of the entire series come from Majora’s Mask, but I’ve chosen to focus on a handful of them that left the greatest impression on me, and made connections to other in-game characters and real life lessons: the conversations with the Moon Children at the end of the game.

The five children you meet inside of the moon are extremely thought-provoking characters. Albeit off-putting, they seem mostly innocent, running around a vast, open field, wanting someone to play with (except for the child in Majora’s Mask, sitting alone). However, with their faces hidden behind the masks of the four bosses and Majora’s Mask itself, there’s an almost disturbing dichotomy presented between the innocence of childhood and the evils of Majora’s magic, which in itself is something to stop and consider. Why are the faces of the five children covered by the grotesque masks of Odolwa, Goht, Gyorg, Twinmold, and Majora? If you look closely, the sides of their heads appear similar to the Happy Mask Salesman – could it be that these children are representations of him? The darkness embodied by the masks, covering the faces of children resembling a character we have come to trust, suggests there may be two sides to the Happy Mask Salesman’s coin, and that there is another side to him and his motivations. The imagery seems cautionary against putting blind faith in the Happy Mask Salesman just because he’s presenting himself as a friend, a lesson that extends beyond the game – people are not always as they present themselves to be, and naive trust can open a Pandora’s Box of problems.

The child wearing Odolwa’s mask asks Link, “Your friends… What kind of… people are they? I wonder… Do these people… think of you… as a friend?” In our real world outside of the fictional world of Termina, friendship is one of the most important parts of our lives, no matter how few or many friends we have. But the question the Odolwa child poses is something we may not often consider: What kind of people are your friends? Why are you friends? Would they tell other people you are their friend, or would they say otherwise? The child’s inquiry speaks to one of the game’s overarching themes of friendship versus loneliness, which characters like Skull Kid struggle with throughout the entire game, but it also explores the issue of true friendships versus friendships of convenience. Do your friends value you for you, or do they value you for what they can take from you, without having to give much of anything in return?

Skull Kid loses sight of his friendships with the Four Giants, Tatl, and Tael once possessed by Majora, in an allegorical tale of losing sight of yourself and the people that matter when faced with temptation. Skull Kid was tempted with power, in a world where he felt devoid of any and felt ignored, despite the fact that Tatl and Tael thought of him as their friend. The overwhelming pull of Majora’s Mask consumed him and turned him into a dark, twisted version of himself, willing to hurt the people he cared for while under Majora’s influence; Skull Kid’s mischevious, playful personality was warped into something more devious, hurtful, and sinister, amplified by the hate embodied within Majora. The Four Giants left Skull Kid once he became consumed by the influence of Majora, and Tatl and Tael became the focus of his verbal and physical abuse rather than of his companionship, used and manipulated when he needed them, all the while being used and manipulated himself. When we lose ourselves to material temptations or the allures found in false friendships, in a way we become Skull Kid, unknowingly taken advantage of until we become “puppets” whose “role has just ended.” Once Skull Kid is freed of Majora’s Mask, he tells Link that “friends are a nice thing to have” and asks him to be his friend, too, which helps to redeem his character by suggesting that despite losing his way, he now truly values the ones closest to him after having lost them due to his own mistakes but being fortunate enough to have been forgiven.

While the Odolwa child explores the question of friendship, the Goht child delves into the subject of happiness, asking Link, “What makes you happy? I wonder… What makes you happy… Does it make… others happy, too?” In this age of extreme narcissism and focus on the self over the bigger picture, we often lose sight of how our actions affect the people around us, especially the ones we’re closest to. We’re often told to “do what makes you happy,” but hardly in conjunction with considering others’ feelings. But should we? Should we pursue what makes us feel good and brings us joy, regardless of how it might affect who we care about, or is part of our responsibility to those people to consider them, even when we feel we must make choices for ourselves? This question ties into the Gyorg child’s question to Link: “The right thing… what is it? I wonder… if you do the right thing… does it really make… everybody… happy?” When faced with making hard decisions, we often rationalize our choices by putting a positive spin on them, confusing and intertwining what makes us happy with what’s right. But the same questions come into play as before: do we consider the people closest to us when making what we feel are the “right” decisions for ourselves, or do we act in our own self-interest, even if our idea of what’s right conflicts with the feelings of those same people? Do we know what’s right versus wrong better for ourselves than anyone else?

Given the fact that masks are the central focus of Majora’s Mask, the Twinmold child asks a rather pertinent question: “Your true face… What kind of… face is it? I wonder… The face under the mask… is that… your true face?” Link dons quite a number of masks in this game, some of which merely give him abilities, but others that transform him completely. The Zora and Goron masks contain the spirits of Mikau and Darmani, influencing Link’s appearance when he transforms, while the Deku butler sees much of his son in Link while he wears the Deku mask. So in this alternate universe where denizens from Hyrule appear as completely different people in Termina, which Link is the real Link? Is Link still the same boy he was in Hyrule, or is his true self locked within one of the masks? In our world, we often struggle with the issues of wearing different masks around different people – how you present yourself to your parents may not be how you appear to your friends, and that persona may differ from who you are with your significant other. Perhaps you never feel the need to wear a mask, and your true self is always present, or maybe there’s only one person with whom you feel comfortable removing all guises. Who are we? Are we actually one of the masks we wear on a given day, or are we none of them? Do we lose our true selves to the facades we create, or were we never aware of who we were before we started wearing the masks? Perhaps we wear them for fear of showing people who we are inside, and end up pushing away the same people we were trying to bring closer by pretending to be something we’re not, when they would accept us for who we really are under the masks.

The Moon Child wearing Majora’s Mask is different from the children wearing the bosses’ remains – he’s somber and sits alone under the tree in the field, and when you’ve given away all your masks to the others, he asks, “…Everyone has gone away, haven’t they?” Interestingly, this echoes Skull Kid’s loneliness at being abandoned by the Four Giants and wanting nothing more than friends. However, after realizing Link is the only child left and that he no longer has masks, the Moon Child says, “Let’s play good guys against bad guys… Yes. Let’s play that. Are you ready? You’re the bad guy. And when you’re bad, you just run. That’s fine, right?” Just as the evil in Majora warped Skull Kid’s sorrow into a more wrathful, destructive force, similarly the Moon Child wearing Majora’s Mask seems to turn his disappointment on Link, and into the much more deadly “game” of the final battle between Majora and Link. The Moon Child also identifies Link as being the bad guy – is this because he sees Link as the reason why all of the other children have gone away?

The Moon Child wonders whether it’s fine for the bad guy to run, and doesn’t even question whether or not to fight back; the person arbitrarily labeled as “bad” is left little option but to run away from the person identified as “good,” but our notions of good and bad are turned upside down as Majora declares Link, and not himself, to be the enemy. Link – and the player – know that Majora is an inherently evil force, and that Link is no bad guy, but we may find ourselves fighting our own internal battles with whether or not we consider ourselves to be good people, especially if we are told or made to believe otherwise by someone else. Sometimes we may feel like Link, suddenly told we’re the bad guy when we were sure we made all of the right decisions, skewing our perspectives of ourselves – which comes back around to the Gyorg child’s question of right versus wrong, doesn’t it?

There are no answers given to any of the Moon Children’s questions, because it’s up to you to answer them for yourself. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask shatters the notion that video games are shallow and uncultured by opening up one of the most sophisticated conversations about humanity that I’ve encountered in a video game. Maybe exploring these questions will help you reach your own Dawn of A New Day.